Trained on Epsom Downs

THE LIFE AND TIMES OF ECLIPSE

Part One

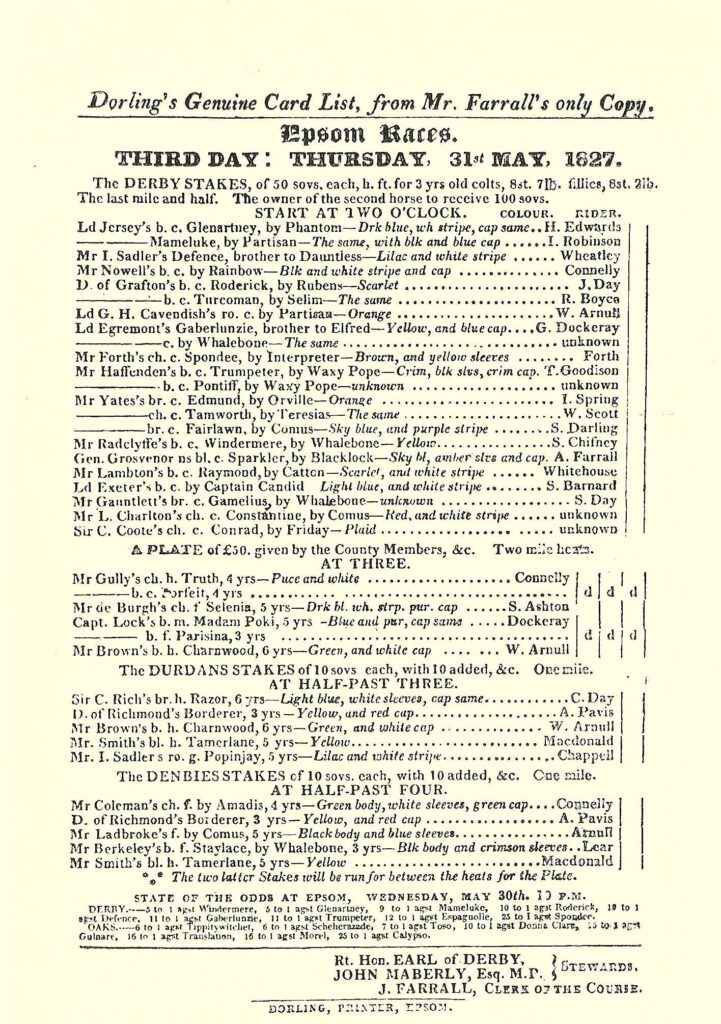

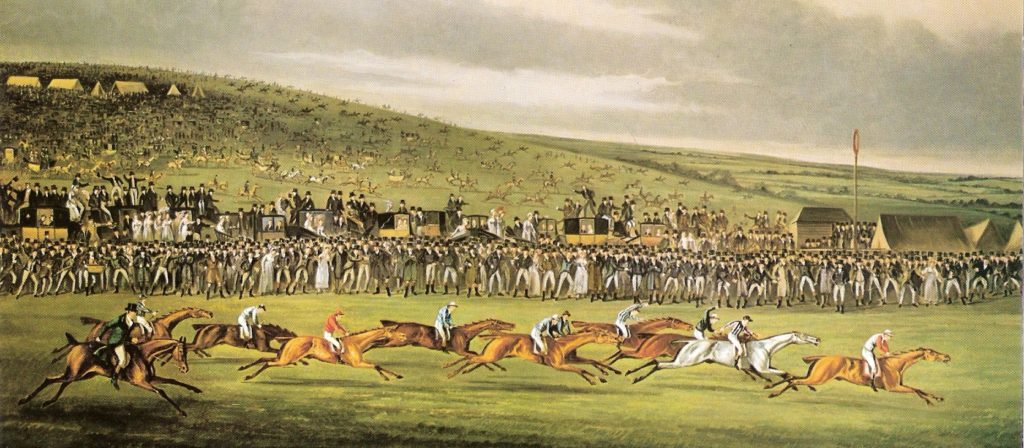

On Wednesday, 3 May 1769, the third day of Epsom’s six-day meeting, Eclipse ran his first race in the Nobleman and Gentleman’s Plate. This, a typical competition for the time, was open to five and six-year-olds and run in four-mile heats. Between heats, 30 minutes would be allowed for the ‘rubbing down’ of horses and the Plate would be awarded to the winner of two heats. If the race needed three heats to decide and had three different winners, a further heat would be run. Any horse that was a distance (240 yards) behind a heat winner would be eliminated, the rules also stipulating, that any jockey who “shall or do, whip or lay hold of any rider, his horse, saddle or bridle”, would be regarded as being distanced.

To set the scene, races in the mid-eighteenth century horses rarely ran before they were four years old. The most prestigious events were the King’s Plates. Eighteen were contested in 1769, with three being at Newmarket. These were usually run in heats over four miles for horses not older than six and carried a prize of 100 guineas.

At this time, there were 92 racecourses operating in Britain. Newmarket held ten meetings a year, while the others would host only one or two. Meetings often began on the Monday and continued through to Saturday. The number of races run each day would vary, but often there would be three, interspersed with cock-fighting and, on occasions, bare-knuckle boxing.

For his debut, Eclipse, then a five-year-old, carried 8st 7lb, while the six-year-olds carried 9st 3lb; the value to winner was £50. In opposition to Eclipse were two five-year-olds, Gower and Tryal and two six-year-olds, Chance and Plume.

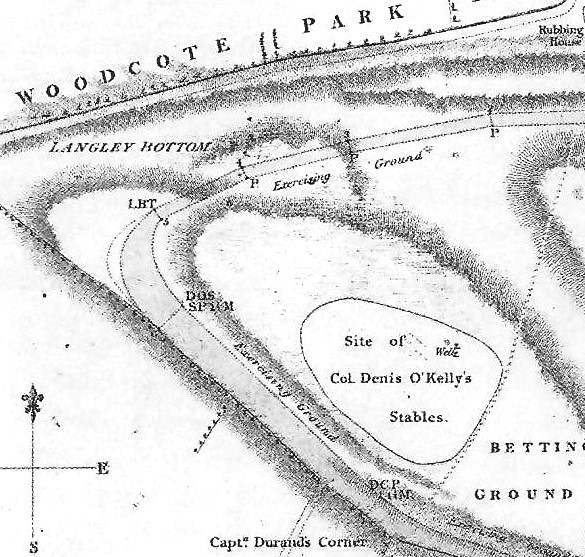

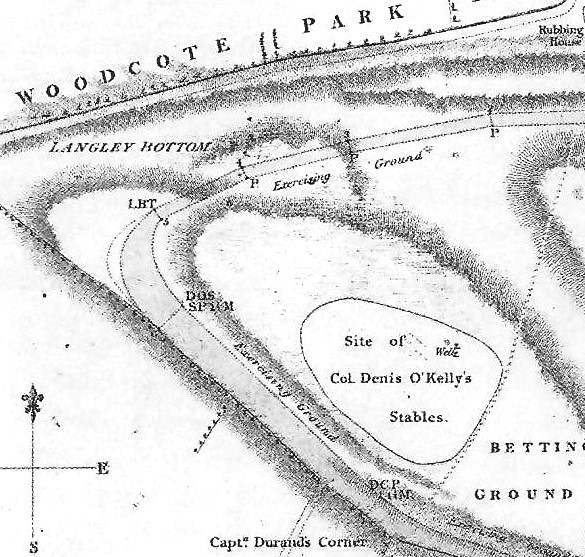

Significantly, before Eclipse ran his first race, Dennis O’Kelly, an Irish adventurer, had purchased both a house and stables situated on Epsom Racecourse, these were between the future first mile and a half Derby start and the present one, (See stables marked on map below). Local news of Eclipse having preceded him, forced his odds in to a skimpy 1-4, although O’Kelly had previously made a large wager at a better price.

In the first heat, Jack Oakley, as planned, allowed Eclipse to go on as he pleased, sitting quietly in the saddle, while making no attempt to hold him up. Eclipse taking an early lead, then drew further away from the opposition.

Before the second heat, O’Kelly, made two large bets at 6-4 and Evens, that he could forecast the correct order of all five runners. To the surprise of the layers, when asked for the order he replied “Eclipse first, the rest nowhere”, implying, Eclipse had to finish a distance (240 yards) ahead of all his rivals.

The second heat off and running, all five runners were grouped closely together at the three-mile post, then Oakley let Eclipse draw away to fulfil what has become a famous racing prophecy.

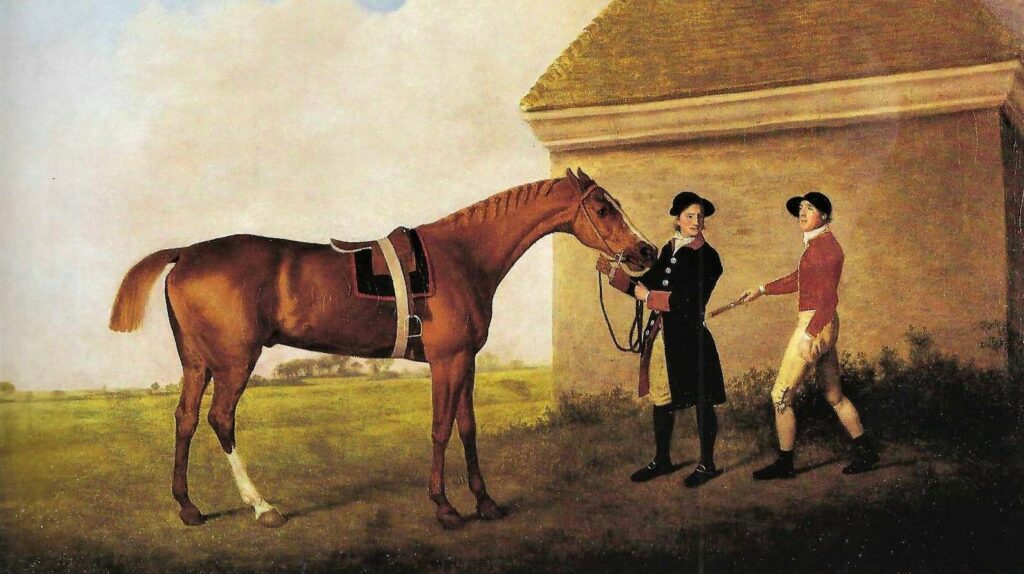

The birth of Eclipse was entirely in keeping with the legend he was to become.

Foaled at noon on Sunday, 1 April, 1764, in a paddock near Cranbourne Tower in Windsor Great Park, his birth coincided with an annular eclipse – an eclipse of the sun in which the moon, seen projected on the solar disc, leaves a golden ring of light visable. Writers of the day called it “The Great Eclipse”.

The breeder of Eclipse was William, Duke of Cumberland (1721-65), the second surviving son of George II. A professional soldier, Cumberland was a Major-General at the age of 22 and, in the company of his father, was seriously wounded when defeating the French at Dettingen in Bavaria, this the last battle where an English king was present.

In 1745, Cumberland was promoted to Captain General of the allied army in Flanders and, the following year, defeated “Bonnie Prince Charlie,” the Young Pretender, at Culloden Moor, Inverness. So severe was his crushing of the Stuart rebellion that he gained the nickname Butcher Cumberland. However, in 1757, when head of a Hanoverian army, he was defeated by the French at Hastenbeck, after which he resigned all his military commands.

Cumberland, a dedicated and ruthless soldier, now transferred his passion to the Turf. Already an early member of the Jockey Club and the only royal member (his colours were all purple), he took up the position of Ranger of Windsor Forest, where, from his Cumberland Lodge residence, he set up his Windsor Forest Stud.

Within seven years he had bred the two most influential racehorses in the history of thoroughbred breeding – Herod (b.c. 1758), the eight-time Champion Sire 1777-1784 and Eclipse.

The sire and dam of Eclipse were both in the ownership of the Duke of Cumberland at the time of their mating. Spilletta (b.f. 1749), was a good-looking daughter of the eight-time Champion Sire, Regulus and purchased by the Duke from Sir Robert Eden. Beaten in her only race at Newmarket in 1754, she was later sent to the Duke’s Stud. Altogether, she produced five foals before her death in 1776, incl. Proserpine (b.f. 1766) and Garrick (ch.c.1772) also by Marske.

Although just below top class, Marske won three times, his most notable victory coming in the Jockey Club Plate, when, as a four-year-old he beat Brilliant over Newmarket’s Round Course (3 miles, 6 furlongs and 93 yards). However, at Newmarket in 1756, when twice matched against the future Champion Sire, Snap, he was beaten both times.

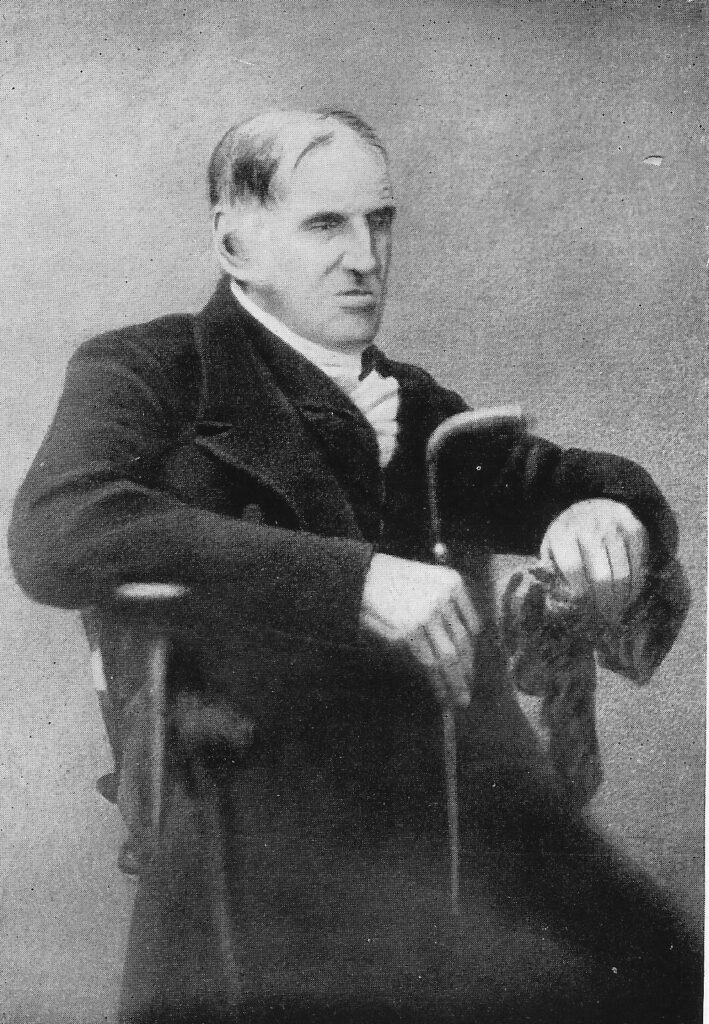

Before the Duke’s death, Marske was considered of little value as a stallion, commanding only a half-guinea fee, and at the subsequent dispersal sale, he was sold to a Dorset farmer for a trifling sum. However, also attending the sale was William Wildman, a large-scale grazier and meat salesman at Leadenhall Market, who raced for a hobby, keeping a small stud at Mickleham in Surrey. On his arrival, he found that Eclipse had been sold for 70 guineas before the advertised time of the sale. His forthright objection caused the lot to be put up again and this time Wildman secured Eclipse for 75 guineas.

Mindful of the Dorset farmer after Eclipse’s sensational victory at Epsom, Wildman, paid him a visit, and on the exchange of £20, returned home with the sire of Eclipse. Thereafter, the success of Eclipse boosted Marske’s popularity and he went on to become Champion Sire in 1775 and 1776. Finally purchased by Lord Abingdon, he stood at his Rycot Stud in Oxfordshire, for the then enormous fee of 100 guineas. Marske died in July 1779, aged 29 years, having sired the winners of 352 races.

Mr Wildman, realising he had obtained a bargain, decided to allow Eclipse time to mature. Of some concern, however, was the horse’s temper, at one time so bad, that Wildman considered having him gelded. However, after due consideration, he sent him to George Elton (or Ellers), a ‘rough-rider’ near Epsom, who rode him about all day and occasionally throughout the night to quieten him down. Although the horse was never vicious, he always kept his fiery temper and, at this stage, Wildman’s first priority was to find a patient jockey. Jack Oakley fitted the bill and was engaged to ride Eclipse in almost all his races.

Part Two

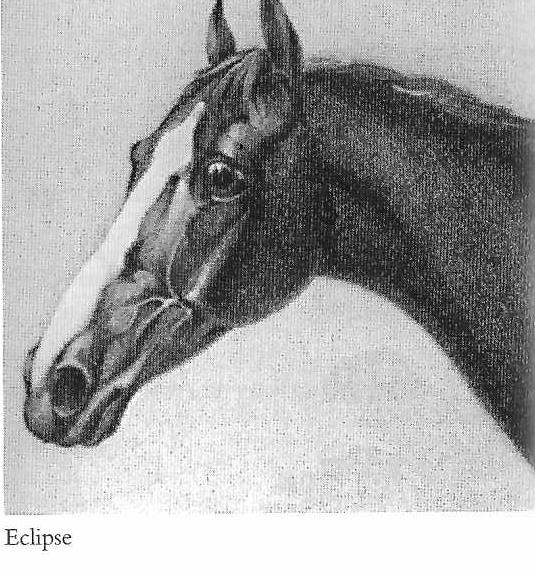

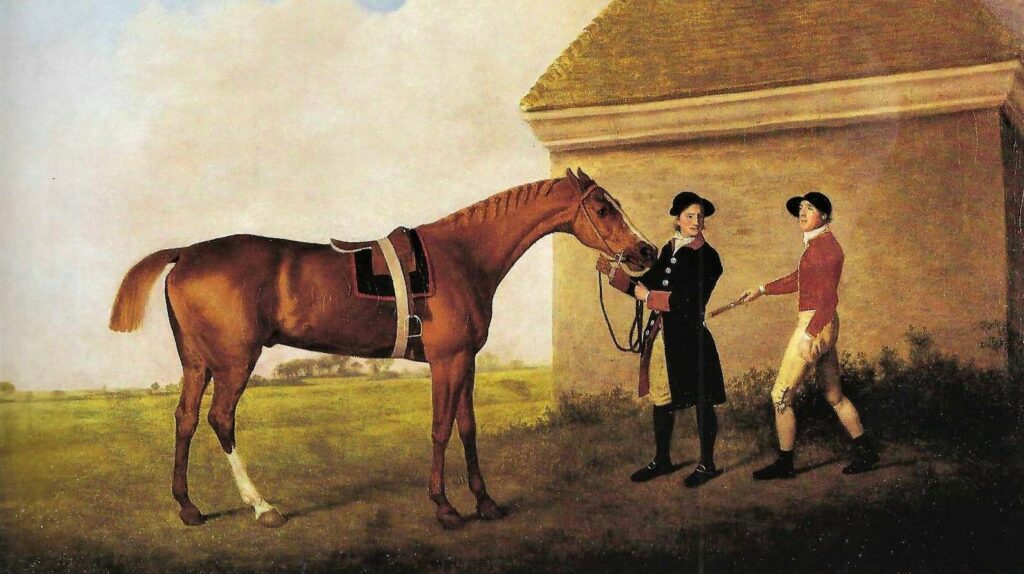

A chestnut horse with a white blaze and a white stocking on his off-hind leg, Eclipse grew to be a magnificent horse, measuring 15.3 hands at the withers. This at a time when very few horses reached 15 hands and Lord Rockingham’s Sampson (1745) by Blaze was recorded at 15.2 hands as “the largest-boned bloodhorse ever bred”.

Other contemporaries complete the picture: Mr John Lawrence, who saw Eclipse and later published a “History and Delineation of the Horse” in 1809, said of him:

“When I first saw him, he appeared in high health, of a robust constitution, and to promise long life. I paid particular attention to his shoulder, which, according to the common notion, was in truth very thick, but very extensive and well placed”.

“His hindquarters and croup appeared higher than this forehand; and in his gallop it was said no horse ever threw his haunches with greater effect, his agility and stride being on a par, from his fortunate conformation in every part and his uncommon strength”.

“He had considerable length of waist and stood over a great deal of ground, in which particular he was of the opposite form to Flying Childers, a short-backed, compact horse, whose reach laid in his lower limbs . . . Eclipse was thick-winded , and breathed hard and loud in his exercise . . . “

Mr William Percival, a noted veterinary surgeon and lecturer, wrote:

“He was a big horse, in every sense of the word, tall in stature, lengthy and capacious in body, and large in his limbs. For a big horse his head was small and partook of the Arabian character; his neck was unusually long; his shoulder was strong, sufficiently oblique, and although not remarkable for, not deficient in depth. His chest was circular; he rose very little on his withers, being higher behind than before; his back was lengthy and over the loins roached; his quarters were straight square and extended ; his limbs were lengthy and broad, and his joints large; in particular his arms and thighs were long and muscular, and his knees and hocks broad and well formed .”

To keep his exceptional race-record alive, following Eclipse first heats at Epsom, he next ran at Ascot on 29 May, again in a Noblemen and Gentlemen’s Plate worth £50, but this time in two-mile heats. Only Mr Fettyplace’s five-year-old bay horse Cream de Barbale opposed him, with both carrying 9st 3lb. The betting was long odds-on Eclipse, who duly won both heats. Shortly afterwards Dennis O’Kelly bought a half-share in him for 650 guineas, although for betting purposes Eclipse continued to run in Wildman’s name.

On 13 June, Eclipse won his first King’s Plate. Run at Winchester, in four-mile heats for six-year-olds (horses a year younger were permitted to run, but all carried 12st. 0lb). Eclipse won both heats and the 100 guinea-prize, beating Slouch, Chigger and Juba, with O’Kelly’s other runner, Caliban, and Bailey’s Clanvil both distanced in the first heat. Two days later at the same meeting, Eclipse walked over for the City Plate, winning a further £50.

On 28 June, Eclipse walked- over for a King’s Plate at Salisbury and the following day ran two four-mile heats for the City Plate at the same venue. The conditions of the race required horses of all ages to carry 10st 0lb. Eclipse, starting at odds of 1-8, attracted opposition from Mr Fettyplace’s Sulphur (7-y-o) and Mr Taylor’s Forrester (6-y-o). Forrester was distanced in the first heat and Eclipse beat Sulphur comfortably in both heats.

On 25 July, at Canterbury, Eclipse walked over for the King’s Plate and two days later travelled to Lewes, where, ridden by John Whiting, he defeated Mr Strode’s Kingston in two four-mile heats for the King’s Plate, conceding a year at 12st 0lb.

Eclipse did not race again until 19 September, when he took on Mr Freeth’s Tardy for the King’s Plate in two three-mile heats for five-year-olds at Lichfield. He won both heats at odds of 1-7.

The following year, Eclipse reappeared in a match against Mr Wentworth’s Bucephalus at Newmarket on 17 April. At this time, horses did not officially age one year until 1 May, so both competitors were recorded as five-year-olds. Bucephalus was one of the cracks of his day and Wentworth put up 400 guineas against Wildman’s 600, with the general betting also 4-6 Eclipse.

The match was to be one heat over the Beacon Course of 4 miles 1 furlong, 138 yards, each carrying 8st 7lb. Bucephalus certainly made Eclipse gallop, but he couldn’t beat him and his heroic effort took its toll, for he never raced again. Dennis O’Kelly now persuaded Wildman to sell his remaining half-share for 1,100 guineas and when Eclipse reappeared two days later for Newmarket’s King’s Plate over the four-mile Round Course, he did so in O’Kelly’s colours of scarlet with a black cap.

Eclipse was opposed by Mr Strode’s five-year-old Pensioner, and two six-year-olds – the Duke of Grafton’s Chigger and Mr Fenwick ‘s bay mare Diana, a previous winner of King’s Plates at York, Lincoln and Newmarket. All carried 12st.0lb.

In the first heat, Eclipse beat (in order) Diana, Pensioner and Chigger. Diana and Chigger withdrew from the second heat and the opening betting of 1-10 Eclipse was revised to 6-4 Eclipse to distance Pensioner, which he did easily.

Eclipse now walked over for three King’s Plates: at Guildford on 5 June, Nottingham on 3 July and at York, with S. Merriott aboard on 20 August. Three days later at York, Eclipse turned out for the Great Subscription – one four-mile heat for six-year-olds and upwards, with a value to the winner of £319.10s. He was opposed by two notable horses: Mr Wentworth’s eight-year-old Tortoise and Sir Charles Bunbury’s seven-yearold, Bellario.

Eclipse, now six years old, received 7lb from the other two and was made favourite at 1-20. There was also much interest in taking 4-7 that Tortoise beat Bellario. Eclipse, with Merriott up once more, despatched the opposition, while Tortoise repaid his supporters by beating Bellario.

Jack Oakley returned to the saddle for Eclipse’s final three races. The first, a walk-over for the King’s Plate at Lincoln on 3 September, followed, a month later, by a 150 guineas plate at Newmarket, run in one heat over the Beacon Course. Here the sole opposition came from Sir Charles Bunbury’s five-year-old Corsican, who, at level weights, proved no match for Eclipse, as the betting of 1-70 had indicated. The following day, 4 October, 1770, Eclipse walked over for a King’s Plate at Newmarket.

He had then been due to meet Goldfinder, a six-year old colt by Snap, who had earned a high reputation, previously winning a Cup and 2,000 guineas at Newmarket. Sadly, his intended rival broke down the day before the race.

After two seasons, Eclipse had won 18 races, including 11 King’s Plates, and had retired unbeaten .The opponents were no longer there, and if a horse had occasionally challenged, obtaining odds better than 1-20 would have been difficult. Instead he was retired to O’Kelly’s Clay Hill Stud, near Epsom where his fee was set at 50 guineas. Although it took time, together with Herod, they changed the face of thoroughbred breeding.

For more history of Eclipse see Michael’s Books for Sale.

To see Michael’s interviews go to the foot of About Michael