The Italian Job

This is a story from the golden age of greyhound racing – hugh crowds, highly competitive betting and a stage full of characters that have all but disappeared.

During World War II, Wimbledon Greyhound Stadium was very badly bombed, and in order to continue racing and offer some basic amenities, the authorities moved the traps, winning line and stewards’ box to the opposite side of the track.

Soon after my fourteenth birthday, my parents finally consented to me attending the track on my own, although my wish had been granted with reluctance. First, to get in unaccompanied, I had to pretend to be a year older; secondly, I had to be four years older to bet. But, such was my enthusiasm, I managed to achieve both.

However, first I must tell you of my plan to compile a personal form book, covering a longer period than the racecard. Cutting out the Wimbledon results from the Greyhound Express, I pasted them chronologically into an exercise book and compiled an index, listing each greyhound’s finishing position, his time and the date of the race.

One thing I learnt very quickly was that some dogs, whatever grade they ran in, rarely won, whilst others often ran their ‘Best Recent Time’ when second. I labelled all these as chasers, since many did not like to lead, and if they did, some would idle in front until another dog joined them. My developing plan, which I disguised at school as an applied mathematics project, was to find races where three or four of these chasers ran together, preferably behind one or two fast starters. This scenario, used in Tote forecasts, looked to me like a key to a treasure chest.

After a few weeks of cutting and pasting, I had promised to give myself a month’s dry run, just checking through and making nominal bets on paper to find out if I were on the right track. But having selected five races in the first two weeks, from which I had predicted two straight forecasts and two others in combinations, I found it hard to resist. And so every Wednesday and Friday, throughout Nature Study and Double Woodwork, I would pour over the Wimbledon card looking for races that fitted my plan. After school on Wednesdays, I would take my shilling forecasts and three dog combinations into Charlie Young’s betting room, but on Friday nights I went to the track.

One such night, when I was above an archway on the first bend, one of the regulars who I knew as Tony came over.

“What’cha got in that book kid – all the winners?”

“Sometimes,” I grinned.

But my reluctance to give him any details seemed to heighten his curiosity. And although we would chat about the dogs most Fridays, it was not until the night I landed two forecasts both paying over £3 for two bob a time, that my tongue ran away with me.

Tony was mid-20’s, and wore a long black jacket with sideburns to match; a few years later he would have passed for a teddy boy.

“I’ve got some friends who’d be interested in your system and that book of yours – they might pay good money.”

Naturally, I was flattered by his suggestion and fortunately, I hadn’t given him all the details, for having almost perfected what I thought was a passport to riches, I had no intention of sharing it.

At this time, I think it fair to tell you that the sources of my income were many and varied: six shillings (30p) a week from an early morning paper round; a profitable school bookmaking business; a lawn-cutting and dog-walking service and irregular amounts from collecting manure from the milkman’s horse. But, if my new system stood the test of time, all but the bookmaking business could go.

The following Friday, Laurels semi-final night, Tony introduced me to the gang – all Italians – Berni, Ricardo and Alfredo, whose flashing smiles never quite reached their eyes. When they fell to talking amongst themselves, it was about ‘deals’ and ‘goods,’ and I quickly found out that they supplied the black market – that is, when they weren’t racing or at the dogs.

Alfredo, the main man, bore an air of menace, a black suit, slick black hair and a pitted face. He seemed to know most of the bookmakers and when he made a bet, no money changed hands until after the race. For most of the evening Tony stayed close at hand, as if keeping an eye on me, but after gabbling something about the need for cigarettes and a slash, he disappeared under the stands.

Being a big night, there were ten races, instead of the usual eight – the ninth, fitted my system – a 700 yard graded stayers’ event. On Ricardo’s invitation he bought me a meat pie, a pale ale and then came straight to the point:

“I hear you win money here. A good system Tony tells me?”

“Keeps the w-wolf from the d-door,” I replied, in a desperate attempt to sound cool.

Ricardo smirked, tolerating a stammering schoolboy.

“What’s going to win this then,” he pressed.

“Three with the field’s the b-bet,” I replied.

At eight shillings a time this cost me £2, a very big bet for me, but I did it for bravado, and the pale ale helped. As it happened, the three-dog won easily, albeit as the 6-4 favourite, but the second, one of the five chasers, was the complete outsider and the forecast paid me £7 and change. Aware that Ricardo and Co. were close by, I suppressed both my relief and delight, and, on their suggestion, I joined them at the bar, after collecting my winnings.

“Nice forecast,” they all agreed, until Alfredo cut in with, “How you gonna getta home kid?”

“Train from Wimbledon,” I said.

“We givva you a lift to the station, OK? Tony does the driving.”

“Thanks; saves my legs,” I replied.

Strange words from 14-year-old, but I had had two beers!

Once in the car, Ricardo told me that they ran a tipping service – horses and dogs – for about 40 clients; wiring or telephoning their advices on the morning of the race. Approaching the station, Alfredo half turned from the front seat, his slicked back hair reflecting the orange street lamps along the Alexandra Road,

“Listen kid, we wanna you to give us a copy of your system see. Just a copy you understand, we’ll pay £5, OK.?” He looked at me hard, “OK?” he repeated.

“I’ll let you know next Friday,” I hedged, “and thanks for the lift.” Then, glancing at Ricardo, “and for the beer.”

I scurried through the barrier and down to the platform.

I can tell you, I wasn’t too happy about giving anyone a copy of my system, especially not for £5. Perhaps they thought for a kid I was as cool as a cucumber, but I certainly wasn’t as green.

Throughout the week, I day-dreamed about employing someone like Tony to drive me about in a big car, and then stopping all homework. “Who’d ever heard of a professional punter writing about Roundheads and Cavaliers?”

But when the following Friday came and I had no system written out, I began to get nervous. But what the heck! I couldn’t miss the final of Wimbledon’s big Classic.

Travelling up on the train, I had the idea of missing the first two races, to let the crowd build up while I had a cup of tea outside the station. Then, if I were to go to the other end of the track, they surely wouldn’t look for me there? Twenty minutes later, I caught the red double-decker bus that went to the track. I pulled an old flat cap over my eyes to disguise my age and squeezed through the turnstile to join the crowds that flooded into every available space. The trade papers said there would be catering to suit every taste. Where I was, you had a choice between cockles, mussels and jellied eels served in a dish, with vinegar and crusty bread.

Inevitably, there was a Crown and Anchor dice game going on in the ‘gents’ and at Wimbledon, this was always played with five dice rather than the usual three, the operators paying out on doubles or more to get a better profit margin.

While the third race was being run, I was able to move more easily along the walk-way under the stands. I then hit on the idea of transferring into the main enclosure. This way I would avoid the gang and get a better view of the dogs. I paid the additional five shillings and climbed the stairs. All the seats were occupied, but if I went down lower I could stand on the terrace. No sooner had I found a perfect spot than I felt a hand on my shoulder.

“What-cher got for tonight kid?”

“Oh bloody hell!” I thought, “and I’ve paid for the privilege.”

I straightened up to my five foot three inches and told Ricardo, “A 2-4-5 combination in the next looks good.”

Suddenly, Alfredo appeared on the scene,

“Have you gotta dat system with you kid?”

“Er n-no,” I stammered. “I started writing it but, my pencil ber-oke and Dad said I had to g-get on with my homework.”

It sounded weak, and it was – I hadn’t the nerve to tell him I had changed my mind.

He paused for a while, then enquired, “What’s agood tonight then?”

I told him what I had given Ricardo, and as he walked away to join the queue for the forecast, I breathed a sigh of relief.

The dogs now going into the traps, I rushed up to another forecast window to place my bet. Out whirred six ten-bob tickets, down came the seller’s hatch, the traps sprung open and released a wall of noise.

First I could see, then I couldn’t, pushing, shoving, jumping up and down and then falling into the gangway. But I did catch a glimpse of the orange and blue jackets going into the third bend. Scrambling to my feet, I asked, “Who won?” I didn’t have to wait long. A crackly Tannoy annouced “First trap five, second trap two.”

Minutes later, I collected £8 and some silver from the payout window. Ricardo spotted me.

“Well done kid! Alfredo’s got a table upstairs; come and join us,” adding as an afterthought, “make yourself comfortable, you can write that system out for us.”

Surprisingly, Alfredo was in a good mood.

“Good boy, nice divi, come and sit down.”

But then, staring hard into my face, he said,

“Look, I think we stop messing about. I’ma gonna give you £20 and you’re gonna write out the system, OK?”

To soften his order he smiled and handed me a pen.

What could I say? It was twice what my Dad would earn in a week.

For a while, out of stubbornness, I hesitated, until finally, I asked him for two sheets of paper. He waived my request away, spreading four fivers on the table before me.

“Write it out in your book and tear out the pages.”

He then took out a long blade flick-knife and started to clean his nails.

A rage of resentment welled up inside me, and so, with a trembling hand, I started to write.

The system that I gave him was not worth £20; neither was it my system. What I did write was, I hoped, a convincing concoction of selections based on trap numbers and odds, together with a staking plan. Enough I thought to occupy their minds for a few meetings before the truth hit home. We shook hands, although mine were still shaking, and he counted out the dosh.

“Was that your only bet tonight kid?” he enquired, I nodded.

“That’s good,” he said, putting the pages into his inside jacket pocket along with his knife.

“Perhaps we’ll have a little drink later?”

They all got up and moved away, pushing through the crowd. I stayed, feeling what I thought big poker players felt when they’d bluffed a big pot.

Over the next half-hour, I remained at the table reading my torn book. At intervals a crowd would rush out and then back in again; the alternating babble and roar coming and going like a tide. A Tannoy voice announced the weights for the Laurels and, walking down to the lower terraces, I was able to get a good look at the dogs in the parade.

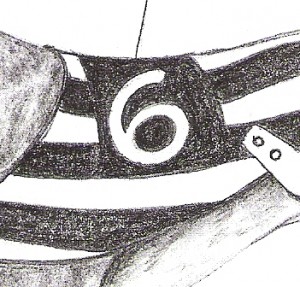

Last year’s winner, the brindled Ballymac Ball, looked a picture. Trained by Stan Martin at Wimbledon and drawn again in Trap 6, he would be difficult to beat. At 14, as now, nothing focused my mind faster than the anticipation of the traps opening.

Last year’s winner, the brindled Ballymac Ball, looked a picture. Trained by Stan Martin at Wimbledon and drawn again in Trap 6, he would be difficult to beat. At 14, as now, nothing focused my mind faster than the anticipation of the traps opening.

Instantly, Ballymac Ball hit the lids and from the shrieks, yells and cheers that followed, you would think that everyone in the stadium had backed him.

A minute later, I was legging it out on the street. All I wanted now, was to get on the train and get home. From over the railway bridge, and halfway down the Alexandra Road, I had 10 minutes to catch my train.

Suddenly, a black sedan pulled up alongside me. Ricardo leaned out.

“Get in the back kid.”

The back door swung open. Fearing they had rumbled me already, I slid on to the back seat. The door closed with a sickening thud.

“Saw you striding out kid – didn’t want you to miss your train – great dog that Ballymac Ball eh? We cleared two ‘C’s’ on him.”

They pulled up at the station. I trapped out of the back seat.

Aboard the train, I re-thought the situation.

“What had I done?”

Here was a racy, black-market gang in the big-time, wanting me in and I’ve just double-crossed them – out of the frying pan into the fire!

From then on, Friday night followed Friday night, but I never returned to Wimbledon Stadium until the Laurels Final the following year.

What happened to my well crafted system? It served me well for a few years – but more of that another time. As for my pseudo system, I often wondered if I had been rumbled, or if the gang had moved on, until nearly a year later when Uncle Albert excitedly burst into our kitchen.

“You won’t believe it, but I’ve found a great way to make money,” he said.

“Oh no” Mum replied, “not again.”

“I have,” Albert continued, “and it’s just up Michael’s street – have a look at this.”

He handed me two typewritten sheets.

“It’s a greyhound system,” I exclaimed.

“Yes, yes, read it,” he said.

“I’ve seen something like it before,” I said slowly.

“No, no, you can’t have; it’s a new system, I’ve just paid £5 for it – it never fails. An Italian geezer at Wimbledon has made a fortune with it!”

This story is from Michael’s book Born to Bet,

of which he has a few signed copies for sale.

The illustrations throughout the book are by Julia Jacs