EVERYMAN’S DERBY DAY HOLIDAY

Towards the end of the 18th century, Derby Day had established itself as not only a major sporting event, but also “The Everyman’s Derby Day Holiday”, with or without their employers’ consent. The Times summed it up in 1793, when cynically reporting:

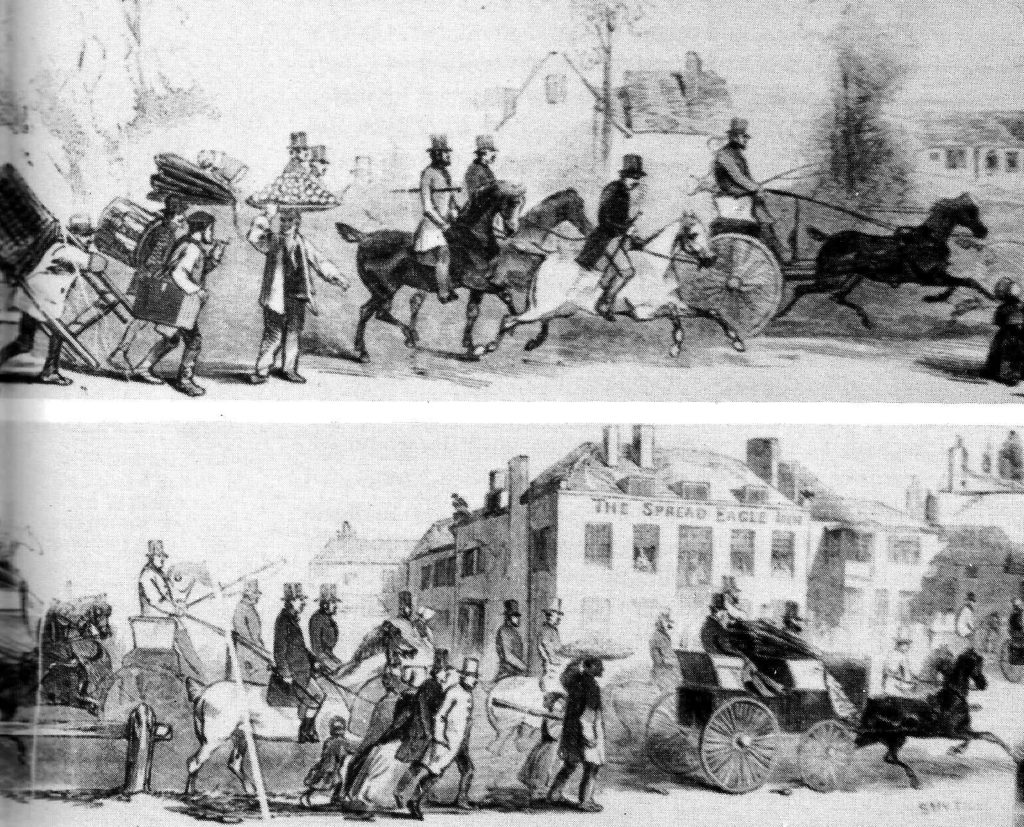

“The road to Epsom was crowded with all descriptions of people hurrying to the races; some to plunder and some to be plundered. Horses, gigs, curricles, coaches, chaises, carts and pedestrians covered with dust crowded the Downs, the people running down and jostling each other as they met in contact. Hazard, cockfighting, E.O. and faro assisted in plucking the pigeons, and the rooks feathered their nests with the plunder.”

The fascination of Derby Day attracted the aristocracy and the workman equally, shoulder to shoulder for the day, and the flow of ready money proved a magnet to both while in pursuit of a good time. Various gambling games were played inside the sprawl of tents across the Downs. Hazard was the most popular dice game and the forerunner of the American Craps game; E.O. (Even and Odd), was a simplistic, but often rigged form of roulette, while Faro was a card game where players would bet against the dealer on what cards he would turn up. The latter, popular in the wild west of America and in the early casinos, was later withdrawn due to the slim margin in favour of the House. Through all this, drunkenness was rife from morning until night.

Although the illegal bare-knuckle boxing matches were difficult to track down, they were extremely popular. The exact venue on the Downs, however, would be a closely guarded secret until just before the fight. One account from Bell’s Life in 1822 reported:

“To gratify the plebeians and commoners, a subscription purse of £25 was collected for a fight between Dick Curtis and Cooper the Gypsy. It took place in the railed hollow where the plate horses saddle, and in the hurry to encircle the field of blood, hundreds of elegant females had a peep if they chose, as they were snugly wedged in…”

Research confirms that Curtis won the fight in about 30 minutes with much skill and science displayed by both boxers. For good measure another interesting fight took place that afternoon, although it was not reported until 1876, when Thomas Coleman’s “Recollections” were published in Baily’s Magazine.

“After the races, there was a prize-fight between a Jew named Moses and another, both regular fighting men. They fought in the bottom, near the old two-mile post, and the Duke of York was there on a splendid brown cob – such a beauty! About 15 hands high, clean shaped, and such power, with a beautiful head. The Duke (owner of Derby winner, also called Moses), was not so tall as his brother, George IV, but more corpulent – ran more to middle – appeared to enjoy the fight much, and as, round after round, those by the ring kept calling out,’ Well done, Moses! – go it again, Moses!’ seemed to be pleased and enlivened at the sound of the word, cast up his head and gave a sort of puff with his mouth.”

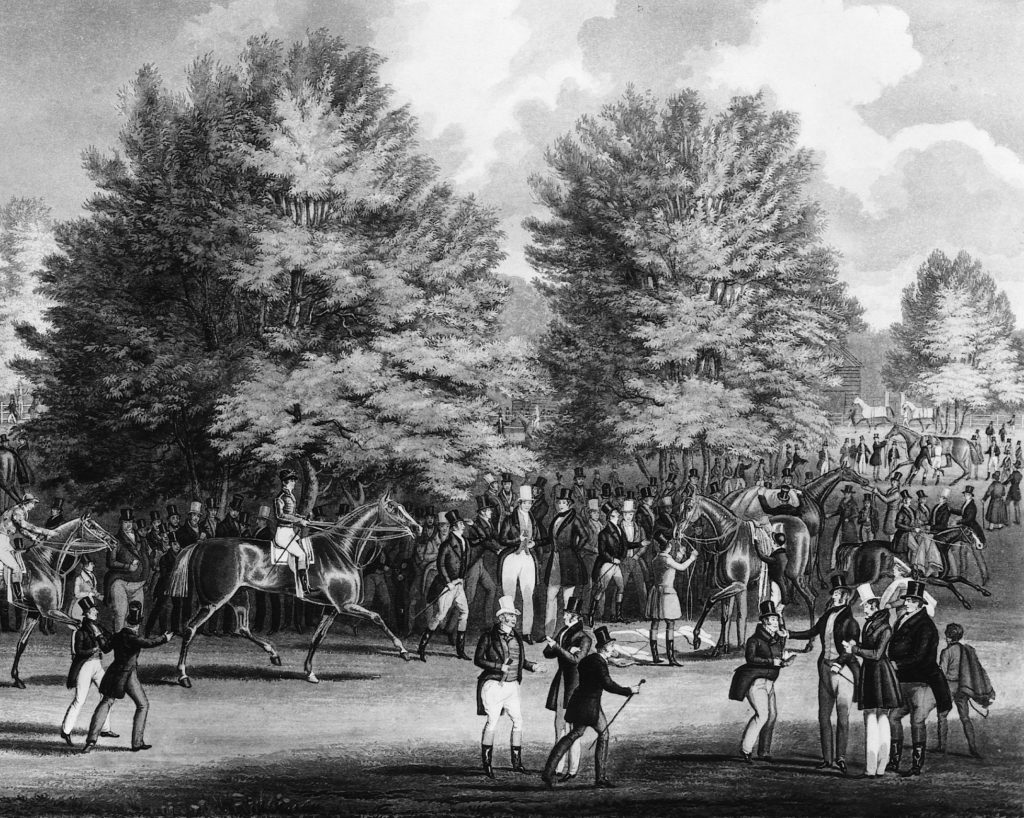

Incredibly, the attending masses at the time knew very little about the horses, the times of the races, or the results. The serious betting on the races was conducted between around two or three hundred nobleman, layers or legs and ‘gentlemen of fortune’, who, on horseback or from carriages, formed a ring around the betting post high on the Downs.

After the 1795, Derby The Times correspondent reported with a lack of merriment:

“The Duke of Queensberry was the principal loser at Epsom races; the noble Duke had his vis-à-vis and six horses, driving about the course with two very pretty émigrés in it. Several carriages were broken to pieces, and one Lady had her arm broken. There was much private business done in the swindling way. One black-legged fellow cleared near a thousand pounds by the old trick of an E.O. table. Another had a faro table, and was on the eve of doing business, when he was detected with a palmed card; almost the whole of what may be justly styled the ‘vagabond gamblers’ of London were present. Mr Bowes, half-brother of the Earl of Strathmore, was robbed of a gold watch and a purse containing 30 guineas at Epsom races, on Thursday last (Derby Day). Many other persons shared a similar fate, both on the same evening and on Friday. Upwards of 30 coaches were robbed coming from the races.”

However, in spite of the published Derby Day warnings, it rapidly grew in popularity. Attendance swelled from around 8,000 in 1795 to ten times that number in 1823, when Bell’s Life (a forerunner of The Sporting Life and first published in 1822), reported:

“By one o’clock there must have been eighty thousand persons assembled on the Downs – what they all went thither for is best known to themselves, but certainly not one twentieth of them saw the race, and the only other amusements were broiling on an arid heath beneath a mid-day sun, or sitting in booths crowded to suffocation amidst the fumes of tobacco and all sorts of hideous uproar…”.

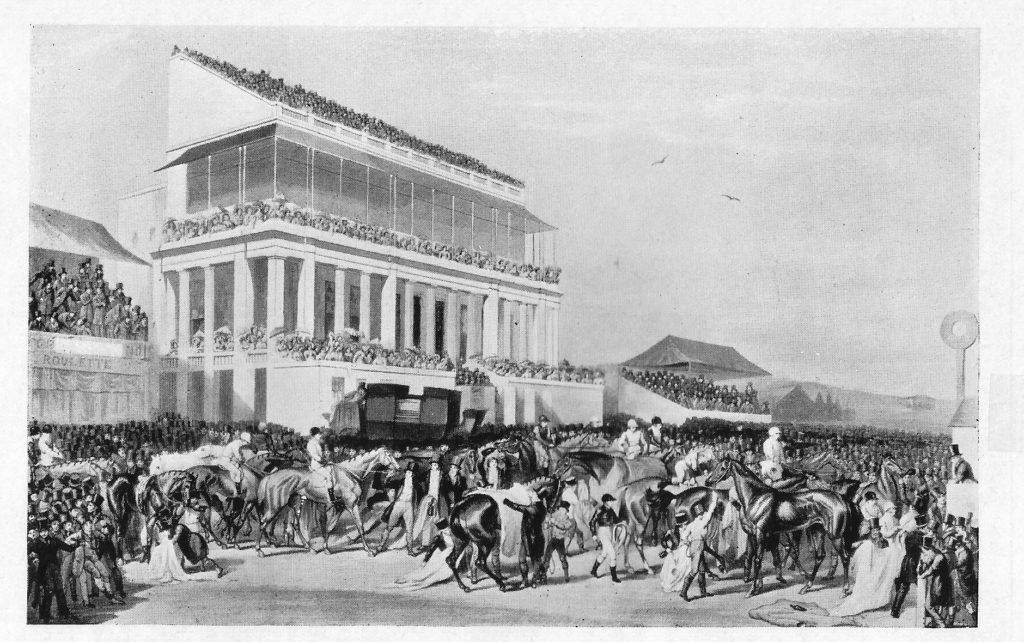

Then in 1829, the first major grandstand was built at a cost of £20,000.

This was raised by 1,000 shares at £20 each, whereupon, the Epsom Grand Stand Association Committee announced:

“The new grandstand at Epsom accommodates 5,000 spectators. It is 156ft wide and 60ft in depth. The columns of the portico are Doric, supporting a covered gallery erected on ornamental iron pillars…the roof contains about 2,000 spectators standing…everyone can see the whole Derby course.”

The Morning Chronicle advised:

“The advantages of which, when compared to the confinement of a carriage, are obvious. Prices of admission: Tuesday and Wednesday, 3s each; Thursday and Friday, 5s each; tickets for the week 12s. The magistrates for the County of Surrey are respectfully informed that they will be admitted free.”

Benjamin Disraeli in his novel Sybil described the scene at the 1837 Derby

“Will anyone do anything about Hybiscus?” sang out a gentleman in the ring at Epsom. It was full of eager groups; round the betting post a swarming cluster, while the magic circle itself was surrounded by a host of horsemen shouting from their saddles the odds they were ready to receive or give, and the names of the horses they were prepared to back or oppose…

“Five and thirty ponies to one against Phosphorus.” shouted a little man vociferously and repeatedly. “I will give you forty.” said Lord Milford. No answer – nothing done.

“Forty to one!” murmured Egremont who stood against Phosphorus. A little nervous, he said to the peer in the white great coat, “Don’t you think that Phosphorus may after all have some chance?” “I should be cursed sorry to be deep against him,” said the peer. Egremont with a quivering lip walked away.

Then, after Egremont decides not to hedge his position, “the ring breaks up, all galloping off to the Warren where the horses are being saddled.” Disraeli then expresses the intense passion of those waiting, as true today for some as then:

“A few minutes, only a few minutes, and the event that for twelve months has been the pivot of so much calculation, of such subtle combinations, of such deep conspiracies, round which the thought and passion of the sporting world have hung like eagles, will be recorded in the fleeting tablets of the past. But what minutes! Count them by sensation and not by calendars, and each moment is a day and the race a life.”

At the fall of the flag, all 17 runners got off to a good start, with The Pocket Hercules the first to show ahead of Caravan, Phosphorus, Wisdom, Benedict and Rat-trap. At the mile post Caravan and Phosphorus took over and at Tattenham Corner drew clear. The duel continued up the straight, where Phosphorus went ahead two strides from the post to win by a head, leaving Lord Egremont a poorer, but wiser man.

1837 Phosphorus

40-1 Derby winner

In 1838, a year after Phosphorus’s victory, the newly opened London and Southampton Railway ran its first ‘Derby Special’, from its London terminus at Nine Elms Station to Kingston, leaving the passengers to walk the remaining seven miles to Epsom!

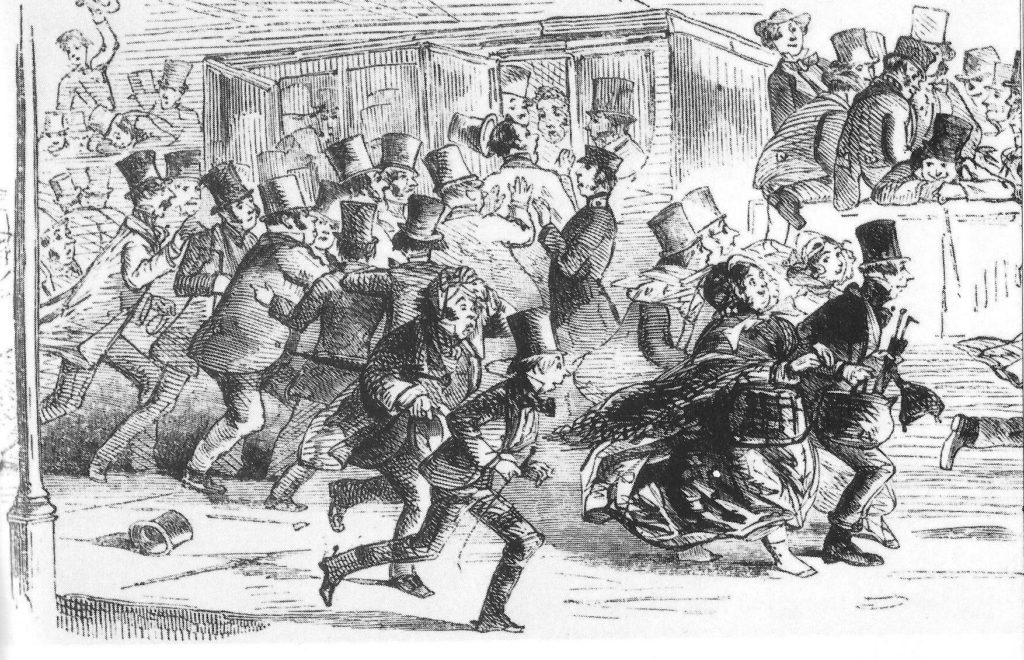

Although the service had been well advertised no-one could have envisaged the thousands of people who waited to board the trains. The station master, guard and porters diligently packed the trains to suffocation, but when their last train left before mid-day and they closed the gates, the remaining crowd, some said as many as 5,000, took their revenge by breaking down the gates and smashing the windows, until a troop of mounted police arrived to restore some order.

The following year, the railway, courageously advertised its ‘Derby Specials’, to depart every 20 minutes. Once again thousands arrived, but those who did reach Kingston were met by cabmen who had doubled their fares to get to the racecourse.

The Derby Day rail chaos continued until, after the merger of the Croydon and Epsom Railway with the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway, a terminal was opened at London Bridge in 1847, followed by a loop line from Waterloo to Epsom.

Even then, stories abounded of passengers bundled into the rear carriages and then stranded, when due to the heavy load, the train pulled away with the front portion only.

But despite the chaos and disappointments, the Epsom attendance grew year on year, as did the excuses given to employers for their absence. Grandmother’s funeral being a favourite, until some ran out of grandmothers! Nevertheless, the popularity of Derby Day became unstoppable, as the Londoner’s day out.